In April 1944, the German Reich’s armaments industry decided to use the salt mine in Kochendorf as an underground factory, protected from air raids. The idea of a second access to the mine arose to ensure the underground armaments factory could remain operational even if one shaft was destroyed in an air raid. Despite objections from mining experts, the Ministry of Armaments approved the construction of a third access shaft at this location. Unlike the vertical shafts, this shaft was designed to slope into the ground at an incline of 20 to 27 percent. This inclined tunnel was intended to enhance the efficiency of the underground factory by enabling the transport of materials and armaments without relying on lifts. Instead, wagons pulled by cable rollers would handle the movement of goods, particularly Heinkel turbines, for which the Kochendorf mine was originally intended.

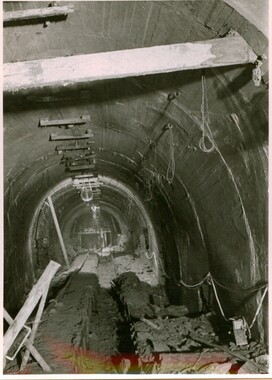

In April 1944, the Reich Ministry of Economics estimated a construction timeline of nine months for the inclined tunnel. Work began about two months later, and within a few weeks, a 32-meter-long preliminary tunnel was completed. Plans included a bunker with a 3.6-meter-thick ceiling to protect the entrance. Technically challenging excavation work began afterward.

Initially, 200 to 300 men worked on and around the tunnel. These included Belgian and Soviet forced laborers, as well as German civilian workers. In October 1944, prisoners from the Kochendorf concentration camp were added to the workforce. These prisoners performed heavy labor, hauling rocks and debris from the tunnel. The SS rented these forced laborers to companies at a rate of 4 Reichsmarks per person per day (skilled laborers cost 6 Reichsmarks).

The worksite at the inclined tunnel was one of the most dangerous labor assignments for the prisoners at the Kochendorf concentration camp. The work was not only physically demanding, but the prisoners also faced constant beatings from *kapos* (prisoner foremen) supervising the work. Additionally, the prisoners were exposed to harsh autumn and winter weather with little protection in their thin prison uniforms. The grueling conditions contributed to Kochendorf’s status as a "death through labor" camp. Many malnourished and mistreated prisoners could not endure the work for long. Although the exact death toll from the construction of the inclined tunnel is unknown, death rates for similar labor assignments in other camps were five to ten times higher than those for factory work.

By the end of March 1945, the construction site was abandoned as U.S. forces approached. At that time, the inclined tunnel was only about one-third complete—roughly 150 meters had been excavated and reinforced. The Organization Todt, responsible for the project, had unsuccessfully attempted to speed up progress by increasing the workforce.

The inclined tunnel is now sealed and filled with groundwater.