In the spring of 1944, the German Reich government decided to convert the Kochendorf salt mine into an underground armaments factory. To facilitate the transport of materials and weapons, two additional access points to the mine were planned. One of these new access points was to be built at this location on the Lindenberg. The site was chosen to ensure the shaft did not directly intersect the underground chambers of the mine at a depth of 200 meters. A tunnel would later connect the shaft to the mine, as a precaution against the risk of water ingress, which mining experts feared could occur with the new shaft.

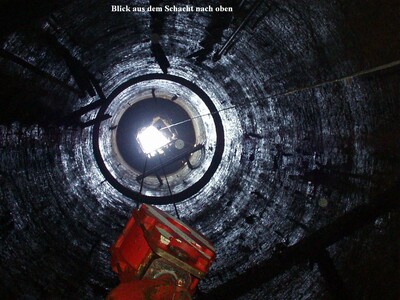

Initial plans for the shaft were presented by the Central Office for Special Mining Tasks in May 1944. These plans included protecting the nearly seven-meter-wide vertical shaft on the Lindenberg with a massive bunker against air raids. There was no plan for an exit on the Lindenberg itself; instead, the exit was to be constructed 170 meters away in the protected valley. This required digging an additional tunnel.

Work on the vertical shaft, referred to in mining as a “Saigerschacht”, began on October 1, 1944. The task was assigned to Vereinigte Untertage- und Schachtausbau GmbH - Veruschacht -, a subsidiary of Hochtief AG. The company faced intense pressure to complete the project quickly, but progress was hindered by shortages of materials and labor. At the start of construction, the local Veruschacht manager, Helmut Broska, stated: "The missing Eastern European workers must be provided to meet the schedule. KZ prisoners cannot be used for the vertical shaft." Although the armaments industry had requested KZ prisoners for the construction and operation of the underground factory, these prisoners, some of whom had been selected for forced labor based on their professions, were generally unsuitable for specialized tasks. They were instead assigned to heavy manual labor.

By December 1944, the plan called for digging 25 meters of the shaft per month, with a target of increasing this to 40 meters. However, the strong influx of surface water delayed progress from the outset. By February 1, 1945, the shaft had reached a depth of only 61 meters. Even greater challenges were anticipated with a water-bearing rock layer at a depth of 100 meters. As the frontlines approached, construction came to a halt. By late March 1945, with the shaft only 87 meters deep, the project was abandoned. On April 13, 1945, Bad Friedrichshall was occupied by

the U.S. Army.

Postwar Developments

After the war, the shaft was initially secured with wooden planks supported by iron beams. Later, a concrete slab was placed over the opening, and the municipality built a playground nearby. In 2003, the shaft was filled in for safety reasons.